While it’s winter and more time than ever is spent indoors staying warm, I wanted to provide some insight into what Detroit used to look like back in the day. The settlement patterns were inspired from both the deep cultural influences of European explorers and the natural landscape. These patterns are still present today and should be understood and remembered in Detroit’s redevelopment.

![1873-Detroit_map[1]](https://www.challengedetroit.org/darinmcleskey/files/2014/02/1873-Detroit_map1-300x228.jpg)

Let’s start with the Ribbon Farms. Apparently in the French system of settlement, pioneers were granted tracts of land originating at a body of water that extended nearly indefinitely into the wilderness. About 20 original settlers were granted land from Cadillac, and most of their names are still prevalent in this city as street names. Campau, Rivard, St. Antoine, Dubois, and St. Aubin are all original land grantees. The French had their fort near downtown and mainly settled/ farmed northeast of that fort. I own a property on Pierce Street near Eastern Market – I’ve researched the deeds all the way to the original land grant, and surely enough it was part of the original St. Aubin Farm.

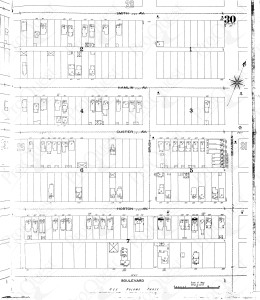

Sanborn maps are another insight into the history of many urban areas. I own a house in the North End, very close to our farm site at the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative. This neighborhood was platted in the 1880s, just after the city limits expanded north of Grand Boulevard. This far (3-4 miles) from the river, farmhouses were often situated on Woodward, extending east and west perpendicular from Woodward. In the case of the southwest corner of the North End, Fannie Horton platted the Horton Farm following the death of her husband. While researching at the Register of Deeds last spring, I even uncovered a special tax assessment for “re-planking” the wood lined roads including Horton and Custer. The above Sanborn Map is from 1897. Housing at this time was about as sparse as it is currently. Many single family homes were built, East Bethnue was then called Hamlin, and Brush street didn’t intersect with Grand Boulevard. There were very few commercial structures – mainly townhomes and larger single family homes. Remember, this was before automobile transportation. That’s probably why nearly all of the older homes were wood construction.

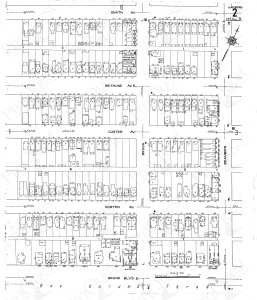

Welcome to 1915. The neighborhood has filled up quite a bit. Nearly every lot has a house on it, and many have flats or apartments fronting the alley. The side streets have townhouses, and there are a few commercial structures. Bethune continues across Woodward now, and Brush Street continues to Grand. Keep in mind this is 5 years after Ford’s Highland Park opened, only 3 miles north of this location.

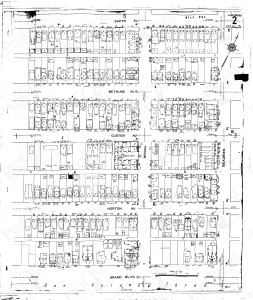

Here’s 1951. The neighborhood is even more full. Filling stations (gas stations) have proliferated through out the neighborhood, and commercial buildings have filled in. “High Rise” apartments have been built in the remaining empty lots and people commonly have garages. Detroit’s economic engine was humming, and this neighborhood was no exception.

Sanborn Maps are often helpful for environmental considerations. Because these maps were created for fire insurance purposes, they shed light into the type of construction, location of buildings, proximity to industrial sites, and often mark underground gasoline storage tanks. In urban farming they help us determine when buildings were torn down, and where we should expect to encounter debris. They show where foundations used to be, and what lots contain native soil. Who would’ve thought that a fire insurance company would eventually be aiding urban farmers. Who would have thought that Fannie Horton’s farm would be a dense community, then revert to farm land? Only Detroit has these cycles of development, and it’s important to remember the past in crafting it’s future.