In all seriousness, this was the opening comment of a diversity panel I attended on my first day with my host company.

The overall fascination with the work ethic, preferences, and general perceptions of my generation (defined loosely as those born from 1982-1998) never ceases to amaze me. It seems a third of the conversation is centered around figuring out this mystifying generation and how to appeal to it from marketing and sales to human resources, while another third angrily denounces the upcoming work population as a lost cause, and the last third, primarily those of us who actually are millennials, are left to defend our generation and prove these claims wrong. (I’ve never heard a millennial say, “Yes, I am lazy, unproductive, and don’t know how to communicate.”)

Regardless of where you fall on that spectrum, as this Charles Schwab blog points out, Millennials surpassed the Baby Boomers as the nation’s largest living generation in 2015 according to the US Census Bureau, so it’s a good idea to gain an understanding of each other. Here are a few of my favorite Millennial Myths debunked:

- Millennials are lazy – This recent blog article in the Huffington Post really says it all, “How can someone who has a degree and work multiple jobs to make ends meet be considered lazy and unproductive?” I suppose this stereotype originated from the perception that Millennials are used to instant gratification in the technology age, and that we expect things to be handed to us

instead of “working our way up.” I would first point out that instant success and hard work are not mutually exclusive. If anything, the entrepreneurial CEOs of startups have had to work just as hard if not harder than many of us starting out in an entry level position, hoping we will get noticed after putting enough time in. Second, I spent the first five years out of college with a bank, averaging 12 hour work days and frequent weekends, because I desired a long term career with a stable company that offered ample room for growth. I would hope many of us can agree 60+ hour workweeks is not “lazy.” Moreover, not only me but many of my Millennial colleagues at the bank shared this sentiment and therefore did not fit the blanketed stereotype that “Millennials frequently want to change jobs” and/or “be entrepreneurs.”

instead of “working our way up.” I would first point out that instant success and hard work are not mutually exclusive. If anything, the entrepreneurial CEOs of startups have had to work just as hard if not harder than many of us starting out in an entry level position, hoping we will get noticed after putting enough time in. Second, I spent the first five years out of college with a bank, averaging 12 hour work days and frequent weekends, because I desired a long term career with a stable company that offered ample room for growth. I would hope many of us can agree 60+ hour workweeks is not “lazy.” Moreover, not only me but many of my Millennial colleagues at the bank shared this sentiment and therefore did not fit the blanketed stereotype that “Millennials frequently want to change jobs” and/or “be entrepreneurs.”

“How can someone who has a degree and work multiple jobs to make ends meet be considered lazy and unproductive?” – Huffington Post Blog

- Money doesn’t matter – This LinkedIn post challenges a few of my favorite Millennial stereotypes, but most important in my opinion is money. It seems like there’s this HR phenomenon amongst companies all over the world that free food and wearing jeans to work is the best way to attract Millennial talent. While those perks are nice I’ll admit, at the end of the day no amount of complimentary slurpies or popcorn is going to repay my student loans. There’s also been countless studies claiming Millennials are more likely to leave a job in which they are not happy, and rank “high-paying job” low on their list of work priorities. First, who wouldn’t want to work in job that makes them happy? Unfortunately for many of us, that is secondary to paying our bills. While I can only speak for myself, graduating college during the worst economic climate since the Great Depression has instilled a deep value for a steady, reliable job, arguably on par with the Baby Boomers. And while many Millennials do value social enterprise and corporate responsibility, is the decision to prioritize this over financial compensation perhaps more influenced by an employee’s background and access to resources? Does their family have the means to support them and provide a financial safety net if needed? Have they worked hard to save money and taken a calculated risk to shift careers into a lower paying position? In my opinion these factors are more important in determining a person’s career choices than assuming preferences based on age bracket.

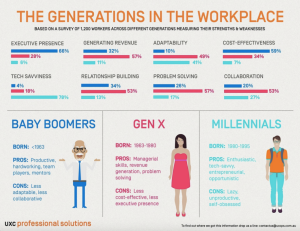

Millennials don’t know how to communicate – “They’re always on their phones.” “It’s impossible to have a conversation with them.” These particular commonplace stereotypes strike me as a complete oxymoron. Technology is quickly becoming the primary method of communication across the globe. And while face to face interactions are invaluable and at times necessary and irreplaceable, more often than not the pace at which we’re doing business today and the global interconnectedness requires us to communicate electronically. Do I prefer to text or email? Yes. Perhaps it’s a result of growing up in an environment where service jobs were categorically outsourced and automated (notably, by the very “cost-saving” baby boomers who are sometimes the quickest to criticize). Nonetheless, in my personal experience communicating electronically enables me to work most efficiently and remain organized. I would suggest that Millennials’ attachment to technology is merely a different form of communicating. And as the above UXC Professional Solutions infographic points out, Baby Boomers are not very adaptable to change.

Millennials don’t know how to communicate – “They’re always on their phones.” “It’s impossible to have a conversation with them.” These particular commonplace stereotypes strike me as a complete oxymoron. Technology is quickly becoming the primary method of communication across the globe. And while face to face interactions are invaluable and at times necessary and irreplaceable, more often than not the pace at which we’re doing business today and the global interconnectedness requires us to communicate electronically. Do I prefer to text or email? Yes. Perhaps it’s a result of growing up in an environment where service jobs were categorically outsourced and automated (notably, by the very “cost-saving” baby boomers who are sometimes the quickest to criticize). Nonetheless, in my personal experience communicating electronically enables me to work most efficiently and remain organized. I would suggest that Millennials’ attachment to technology is merely a different form of communicating. And as the above UXC Professional Solutions infographic points out, Baby Boomers are not very adaptable to change.

Individual stereotypes aside, the most damning case I’ve read thus far addresses the overall problem with generational stereotypes at work, based on a doctoral dissertation of an educational leadership PhD, the findings of which were recently published in “Unfairly Labeled: How Your Workplace Can Benefit From Ditching Generational Stereotypes.”

This research basically concludes there’s not a lot of hard data that supports any of these generational assumptions and the Millennial generation doesn’t actually have any unique attributes. It discusses the tendency to overglorify and overhype the Millennial issue particularly exacerbated by the media to maximize readership. Interestingly, the author points out that “characteristics often attributed to millennials, such as a lack of employee loyalty, extreme technological savviness, aspirational career ambitions, social responsibility, etc., are, if ever, fair characterizations, merely attributes of various life stages.”

This research basically concludes there’s not a lot of hard data that supports any of these generational assumptions and the Millennial generation doesn’t actually have any unique attributes. It discusses the tendency to overglorify and overhype the Millennial issue particularly exacerbated by the media to maximize readership. Interestingly, the author points out that “characteristics often attributed to millennials, such as a lack of employee loyalty, extreme technological savviness, aspirational career ambitions, social responsibility, etc., are, if ever, fair characterizations, merely attributes of various life stages.”

She concludes: “There are a million factors that go into determining the kind of person you are when you grow up, and this arbitrary 20-year-long age bracket that is widely accepted is not one of them.”

Millennials don’t know how to communicate – “They’re always on their phones.” “It’s impossible to have a conversation with them.” These particular commonplace stereotypes strike me as a complete oxymoron. Technology is quickly becoming the primary method of communication across the globe. And while face to face interactions are invaluable and at times necessary and irreplaceable, more often than not the pace at which we’re doing business today and the global interconnectedness requires us to communicate electronically. Do I prefer to text or email? Yes. Perhaps it’s a result of growing up in an environment where service jobs were categorically outsourced and automated (notably, by the very “cost-saving” baby boomers who are sometimes the quickest to criticize). Nonetheless, in my personal experience communicating electronically enables me to work most efficiently and remain organized. I would suggest that Millennials’ attachment to technology is merely a different form of communicating. And as the above UXC Professional Solutions infographic points out, Baby Boomers are not very adaptable to change.

Millennials don’t know how to communicate – “They’re always on their phones.” “It’s impossible to have a conversation with them.” These particular commonplace stereotypes strike me as a complete oxymoron. Technology is quickly becoming the primary method of communication across the globe. And while face to face interactions are invaluable and at times necessary and irreplaceable, more often than not the pace at which we’re doing business today and the global interconnectedness requires us to communicate electronically. Do I prefer to text or email? Yes. Perhaps it’s a result of growing up in an environment where service jobs were categorically outsourced and automated (notably, by the very “cost-saving” baby boomers who are sometimes the quickest to criticize). Nonetheless, in my personal experience communicating electronically enables me to work most efficiently and remain organized. I would suggest that Millennials’ attachment to technology is merely a different form of communicating. And as the above UXC Professional Solutions infographic points out, Baby Boomers are not very adaptable to change.