A few days ago I read an article by Ryan Felton in the Metro Times about the turbulent history of public transit in Detroit. There were a few sections that I thought were interesting:

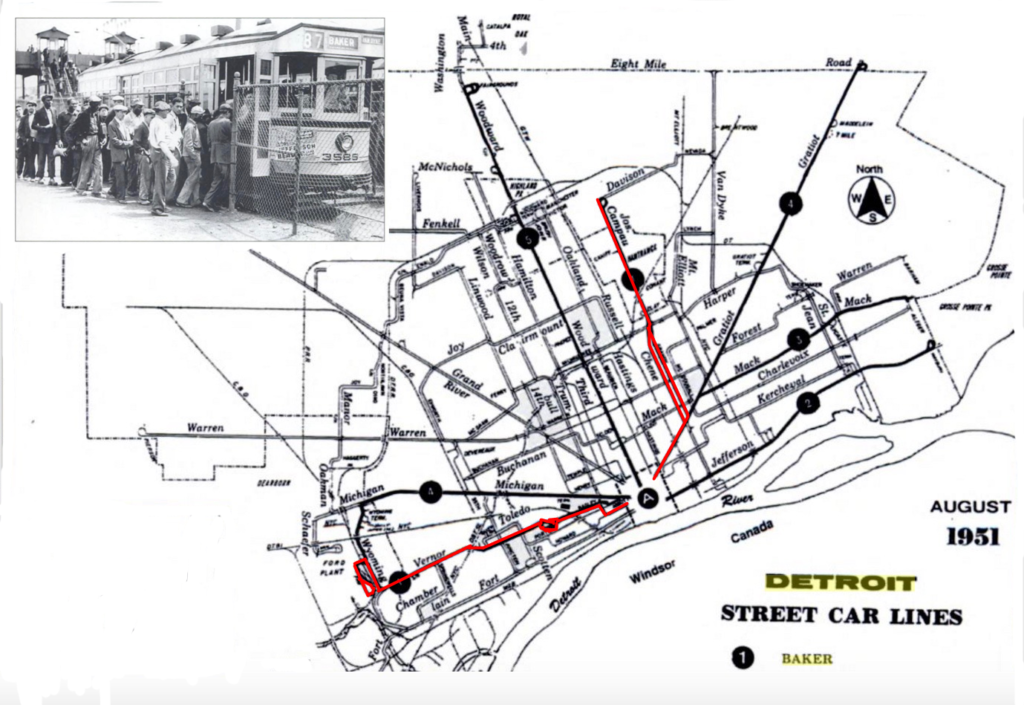

- Back in the 1920s, metro Detroit had nearly 500 miles of streetcar tracks and feeder buses. In the 1940s, there were nearly 1,000 streetcars and 490 million riders (pretty sure that is an annual statistic, but it didn’t specify). However, in the 1950s, rail infrastructure started to deteriorate, transit workers went on strike, and the Department of Street Railways decided to invest in hundreds of buses that would run along the streetcar routes thus rendering streetcars obsolete. The last streetcar traveled down Woodward in 1956. Two months later, President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act which authorized the construction of 40,000 miles of interstate highways literally paving the way for the automobile to take over.

Imagine what metro Detroit might look like today if we continued to invest in streetcars. Isn’t it ironic that roughly 60 years after we determined streetcars to be archaic, our hopes for the future of mass transit in Detroit now cling to a $140 million streetcar line that travels three miles?

Passengers climb aboard the Baker Streetcar (inset top left), which was one of the longest streetcar lines in Detroit in the 1950s.

- Have you ever heard of the regional transit plan proposed in the 1970s? Under this plan, there would have been a Woodward Avenue subway line running from the Ren Cen to McNichols. The service would have then redirected towards Main Street or Washington Avenue in Royal Oak before connecting with another commuter rail service between Pontiac in Detroit. An additional rail would have run along Gratiot Avenue all the way to I-94 before it connected to a commuter line between Port Huron and Detroit. Yet another commuter rail service would have run from Joe Louis Arena to Ann Arbor. Guess what was going to connect these transit options in Downtown Detroit? You guessed it. The People Mover.

Unfortunately, politicians and transit agencies from the city and the suburbs were unable to come to an agreement on a multitude of issues including budget concerns, the specific mode of transportation, taxes, and the merger of various transit authorities to create one regulatory body. While bureaucracy reigned supreme, several decades passed and President Ronald Reagan pulled the plug on a $600 million federal commitment that could have drastically reshaped public transit in Detroit. Eventually, SEMCOG was created and the SMART bus system was instituted. So, instead of a massive public transit system spanning multiple counties we ended up with another bus system and more confusion.

“Almost all of the challenges to the creation of a single regional transit system in metropolitan Detroit can be traced to power asymmetries that manifested in disagreements between the city and its suburbs over money, power and routes.”

– Jan Nelles, Urban Affairs Review

- Initially, the M-1 Rail project was planned to go northbound well beyond city limits. In 2010, the project was scaled back to end at Eight Mile Road. Now, as we are all well aware, construction on the 3.3-mile light rail is nearing completion with the northernmost stop being located in New Center.

“For the second time, an ambitious regional transit plan was reduced to a single keystone project located exclusively within Detroit city limits.”

– Jan Nelles, Urban Affairs Review

The future of transit in the Greater Downtown Area

In Challenge Detroit’s recent project with RecoveryPark, I had the opportunity to build bus stops in the Chene-Ferry neighborhood on the east side of Detroit. While talking with a few bus riders, I learned about some of the frustrations with the current system: not enough shelter or seating at bus stops, safety, cleanliness, unhelpful drivers, and more than excessive wait times. Currently, Detroit has a few government-run transportation agencies including DDOT and the RTA. I have no doubt in my mind that these organizations are trying to do their best on behalf of the tens of thousands of people who rely on public transit to get from point A to point B and back everyday. However, because of a whole bunch of reasons, most of which revolve around money, the bus system in metro Detroit has not been able to operate with much user satisfaction. That brings me to another part of the article I thought was interesting…

One of the bus stop shelters we created at Chene & Warren. As we were finishing construction, an RTA employee pulled over, took pictures and complimented us on taking initiative to improve the public transit experience.

- If we are currently incapable of providing efficiency and reliability to millions of metro Detroiters who use our limited public transit system, how do we expect to do so if the RTA’s new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system gets approved?

“If you can’t manage a bus system [now] how are you going to manage [the new bus rapid transit plan]?”

– SMART Rider, Ferndale Resident, and DIA Employee Jim Smart.

A Current Event

On Thursday, July 21st representatives of Oakland and Macomb counties raised concerns about the RTA’s Master Plan. Specifically, county executives questioned how the regional transit tax would be spent across Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, and Washtenaw counties. The RTA is now trying to address these questions, but only has until August 16th to officially submit the language for the Master Plan to the state.

The Metro Times article mentioned above also made an interesting reference to Johnny Cash. He apparently once told an interviewer “that failure should not be dwelled on. Failure, he supposedly said, should be analyzed, so as to not make the same mistake twice.”

Well, the current “political” path of the RTA’s Master Plan bears striking similarity to the plan created in the 1970s.