This past month, Challenge Detroit decided to allow us fellows to spend our Friday’s in July pursuing an impact project of our choosing, as opposed to working as a group with a non-profit in a pre-arranged style. I decided to work for Healthy Detroit in planning a Community Conversation on Mental Health. While the event is now slated for May 2015, as part of a larger public health conference, the experience has been enriching and better than I could have imagined.

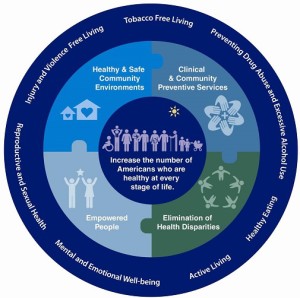

Healthy Detroit is a 501(c)3 non-profit in the city of Detroit that is about 1-2 years old. It is the only organization in the country that is based entirely off the National Prevention Strategy (NPS), which was issued by the Surgeon General in June 2011. The NPS uses a socio-ecological view of health that includes the individual, families, organizations and society working together to produce positive health outcomes. It focuses on the shift to a preventative model of health, as opposed to a treatment model where individuals are treated for ailments, disorders and diseases only once they are fully developed. A preventative model will reduce healthcare  costs across the board while improving the quality of life of people and families. It integrates health into our lives, instead of presenting it like a pill to be swallowed. Read more about the NPS and its four strategic directions and seven priorities.

costs across the board while improving the quality of life of people and families. It integrates health into our lives, instead of presenting it like a pill to be swallowed. Read more about the NPS and its four strategic directions and seven priorities.

One of the priorities of the NPS is mental health and emotional wellbeing. Healthy Detroit is addressing this priority by collaborating with Creating Community Solutions, a part of the National Dialogue on Mental Health, in hosting the Community Conversation on Mental Health event. Small (10-20 people) and large (300 people) conversation events have already occurred across the country and are continuing to be pursued. The Detroit event will be city-wide, with a goal of reaching at least 300 people. Topics will include education, stigma-reduction, identifying issues & brainstorming solutions.

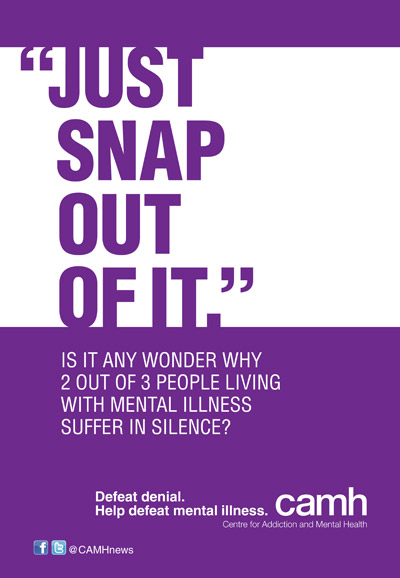

The overall purpose of the conversation is to get a dialogue started about mental health, which is a highly stigmatized and forgotten about issue within healthcare and people’s everyday lives. Mental health is related to how we interact with people around us, understand the world and ourselves. It can lead to low productivity, lost days of functionality, serious disability, and even death. It is highly interrelated with substance abuse and homelessness. Mental illness affect 1 in 4 adults in the U.S. yet a minority of this group will ever receive treatment or support. It wasn’t until 2008 until health insurance companies were restricted from discriminating patients based on their  mental health status. Prior to this, someone who admitted to having clinical depression at any point in their life could be refused services or be charged higher rates at an arbitrary amount. Mental health is also linked to other areas of health. It can change our eating and exercise behaviors, yet changing our eating and exercise behaviors can affect our mental health. Persons with mental health disorders have a lower life expectancy and are much more likely to have multiple chronic physical diseases. The point is, mental health has been historically left out of healthcare systems and public health programming, yet it is a highly prevalent issue and also highly treatable. We should be talking about it and dealing with it, instead of pushing it to the back burner for another day.

mental health status. Prior to this, someone who admitted to having clinical depression at any point in their life could be refused services or be charged higher rates at an arbitrary amount. Mental health is also linked to other areas of health. It can change our eating and exercise behaviors, yet changing our eating and exercise behaviors can affect our mental health. Persons with mental health disorders have a lower life expectancy and are much more likely to have multiple chronic physical diseases. The point is, mental health has been historically left out of healthcare systems and public health programming, yet it is a highly prevalent issue and also highly treatable. We should be talking about it and dealing with it, instead of pushing it to the back burner for another day.

Working on this event has allowed me not only to pursue my professional passion of improving the mental health public health landscape, but I have also been able to work closely with the Healthy Detroit team on other projects, such as their HealthParks pilot program. My main goal when moving to Detroit and starting Challenge Detroit was to find a public health organization, ideally with an element of prevention, that I could work for and contribute to. Not only did I reach this goal, but I learn something new about Detroit every time I work with the Healthy Detroit team. This is an organization that is dedicated to the residents of Detroit and to the public health model of prevention. I couldn’t ask for more.